Dennis L. Taylor 12:01 a.m. PDT July 23, 2014

Wall Street is knocking on the door of Salinas Valley agriculture.

Wall Street is knocking on the door of Salinas Valley agriculture.

Investors from agriculture-focused hedge funds and investment trusts are touring farms in and around Salinas, including vineyards and strawberry fields.

Farmland investments are not new to the agricultural community. For nearly a decade investment managers have scoured the corners of the globe for cheap land as food prices have soared, positioning themselves to profit from the growing demand. Hedge funds now have $14 billion invested in farmland, according to the data provider Preqin.

An increasing number of sophisticated investors and bankers are combining crops and the soil they grow in into an asset class that ordinary investors can buy a piece of.

“It’s a great way to diversify a portfolio,” said Dawn Fiala, a partner and marketing chief for Mesa, Arizona-based private equity firm American Farmland Investments. “Farm investments don’t correlate to commodities or to equity investments like stocks.” Commodities include items such as soy beans and pork bellies.

Called asset classes, investment advisers suggest that an individual investment portfolio should be a mix – some stocks, some bonds, some mutual funds and perhaps some real estate. That way if Wall Street shenanigans cause another great recession as they did in 2008, the investor will be somewhat protected by not having all her eggs in one basket.

There’s a lot to be optimistic about in this new agriculture asset. It was one of the few investments that were not swamped by the 2008 tidal wave, and for a very good reason: people still have to eat, Fiala said.

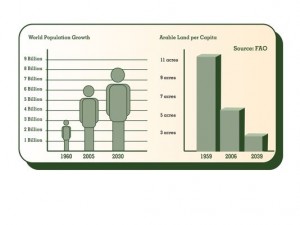

Also, the amount of land that can be farmed is finite, while at the same time global population growth is stretching the planet’s resources even as humans are living longer. By 2030 the world’s population is expected to reach more than 8 billion, compared to the 6.5 billion in 2005.

“By 2030 we’ll be feeling it,” Fiala said.

With that growth comes corresponding demand for food, increasing the value of the land the food is raised or grown on. Fiala’s firm, American Farmland Investments, is predicting a return on investment of between 8 percent and 20 percent. The rolling average 10-year yield of the Standard & Poor’s Index is currently at 8.34 percent.

Increased yields are a key solution to matching demand with food supply. A Yale University study points out that in 1959 it took 11 acres to grow enough food to sustain a person for a year. Today, the same amount of food is being grown on 3 acres.

Here’s how the investment works at AFI, using a purchase in Louisiana that is now in the process of closing as an example.

AFI buys the land and then leases it back to the farmer. The farmer then uses that capital for expansion or equipment replacement or any other needed improvement. In seven years the farmer can buy back the farm from AFI.

On the investor side, individuals purchase units or half-units until the fund has reached 18 units, whereby it will be invested in more farmland. One-half unit goes for $27,750, Fiala said. A purchase in Oklahoma in 2008 has doubled in value, she added.

When asked if her firm is interested in Monterey County farmland, Fiala paused and measured her words.

“We are concerned about the drought,” she said. “We are going to where there’s water.”

But other investors are taking on the risk with the view the state’s water crisis will eventually be resolved. Hedge funds such as American Farmland Co., Farmland Partners and the Gladstone Land Corp. have been nosing around the Salinas and Pajaro valleys looking for potential investments, according to a New York Times article Tuesday.

Like any investment there is always risk. In the same Times article, Jeffrey Havsy, director of research for the National Council of Real Estate Investment Fiduciaries, said that as the trend of farm investment heats up, there is danger of a bubble forming – a green bubble.

“You can certainly overpay for farmland, and if crop prices declined for whatever reason – for example because of some type of natural disaster – there are all sorts of reasons why, all of a sudden, the income stream does not support the price you paid for a piece of land,” Havsy said.

Fiala returned to the facts surrounding the near-future supply and demand for food.

“How could that drop in value?” she said.

Senior Writer Dennis L. Taylor covers agriculture and economics for The Californian. Follow him on Twitter @taylor_salnews.